BAE Systems Developing Smart Skin With Human-Like Sensitivity For Aircraft

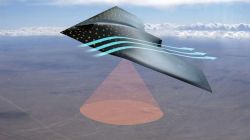

Aircraft could soon become more human as engineers as BAE Systems develop smart skins which can detect injury or damage and the ability to ‘feel’ the world around them.

Engineers at the Advanced Technology Centre are investigating a ‘smart skin’ concept which could be embedded with tens of thousands of micro-sensors. When applied to an aircraft, this will enable it to sense wind speed, temperature, physical strain and movement, far more accurately than current sensor technology allows.

The revolutionary ‘smart skin’ concept will enable aircraft to continually monitor their health, reporting back on potential problems before they become significant. This would reduce the need for regular check-ups on the ground and parts could be replaced in a timely manner, increasing the efficiency of aircraft maintenance, the availability of the plane and improving safety, BAE said on its website.

These tiny sensors or ‘motes’ can be as small as grains of rice and even as small as dust particles at less than 1mm squared. Collectively, the sensors would have their own power source and when paired with the appropriate software, be able to communicate in much the same way that human skin sends signals to the brain. The sensors are so small that we are exploring the possibility of retrofitting them to existing aircraft and even spraying them on like paint.

Leading the research and development is Senior Research Scientist Lydia Hyde whose ‘eureka’ moment came when she was doing her washing and observed that her tumble dryer uses a sensor to prevent it from overheating.

According to Hyde, “Observing how a simple sensor can be used to stop a domestic appliance overheating, got me thinking about how this could be applied to my work and how we could replace bulky, expensive sensors with cheap, miniature, multi-functional ones. This in turn led to the idea that aircraft, or indeed cars and ships, could be covered by thousands of these motes creating a ‘smart skin’ that can sense the world around them and monitor their condition by detecting stress, heat or damage. The idea is to make platforms ‘feel’ using a skin of sensors in the same way humans or animals do.

“By combining the outputs of thousands of sensors with big data analysis, the technology has the potential to be a game-changer for the UK industry. In the future we could see more robust defence platforms that are capable of more complex missions whilst reducing the need for routine maintenance checks. There are also wider civilian applications for the concept which we are exploring.”

This research is part of a range of new systems we are investigating under a major programme exploring next-generation technology for air platforms.