DARPA Flight Tests Fast, Lightweight Autonomous Quadcopter

The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) recently flight tested an unmanned quadcopters to demonstrate autonomous flight without the aid of human operators or global positioning systems.

DARPA announced last week that Phase 1 of its Fast Lightweight Autonomy (FLA) program concluded a series of obstacle-course flight tests in central Florida, flying quadcopters autonomously through cluttered buildings and obstacle-strewn environments at fast speeds (up to 20 meters per second, or 45 mph) using onboard cameras and sensors as “eyes” and smart algorithms to self-navigate.

“The goal of FLA is to develop advanced algorithms to allow unmanned air or ground vehicles to operate without the guidance of a human tele-operator, GPS, or any datalinks going to or coming from the vehicle,” said JC Ledé, the DARPA FLA program manager. “Most people don’t realize how dependent current UAVs are on a remote pilot, GPS, or both. Small, low-cost unmanned aircraft rely heavily on tele-operators and GPS not only for knowing the vehicle’s position precisely, but also for correcting errors in the estimated altitude and velocity of the air vehicle, without which the vehicle wouldn’t know for very long if it’s flying straight and level or in a steep turn. In FLA, the aircraft has to figure all of that out on its own with sufficient accuracy to avoid obstacles and complete its mission”.

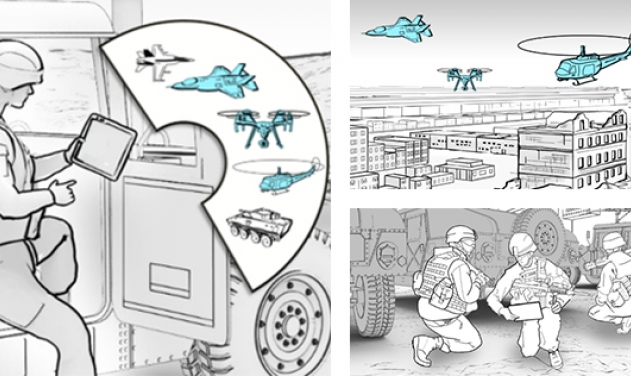

The FLA program is focused on developing a new class of algorithms that enables UAVs to operate in GPS-denied or GPS-unavailable environments—like indoors, underground, or intentionally jammed—without a human tele-operator, the press release states.

Under the FLA program, the only human input required is the target or objective for the UAV to search for—which could be in the form of a digital photograph uploaded to the onboard computer before flight—as well as the estimated direction and distance to the target. A basic map or satellite picture of the area, if available, could also be uploaded. After the operator gives the launch command, the vehicle must navigate its way to the objective with no other knowledge of the terrain or environment, autonomously maneuvering around uncharted obstacles in its way and finding alternative pathways as needed.

The recent four days of testing combined elements from three previous flight experiments that together tested the teams’ algorithms' abilities and robustness to real-world conditions such as quickly adjusting from bright sunshine to the dark building interiors, sensing and avoiding trees with dangling masses of Spanish moss, navigating a simple maze, or traversing long distances over feature-deprived areas. On the final day, the aircraft had to fly through a thickly wooded area and across a bright aircraft parking apron, find the open door to a dark hangar, maneuver around walls and obstacles erected inside the hangar, locate a red chemical barrel as the target, and fly back to its starting point, completely on their own.

The test runs had the combined feel of part air show, part live-fire exercise, with a palpable competitive vibe between the teams. “The range is hot, the range is hot, you are cleared to launch,” crackled the voice of the test director over the walkie-talkies audible in the adjacent team tents, giving a green light to launch an attempt. Sitting under his own shaded canopy, the director followed the UAV’s flight on two video monitors in front of him, which showed views from multiple cameras placed along the course. Metal safety screens, which resembled giant easels, protected the camera operators on the course, as well as teams and course officials, from any rogue UAVs.

Once a UAV was out of visual range, team members followed the progress on monitors. The first successful foray from sunlight through a doorway and into darkness brought a cheer. “It’s in the hangar!” came a gleeful cry over the walkie-talkies. And when a UAV maneuvered successfully around the interior obstacles and reached the targeted red chemical barrel, an official goal observer took to the microphone intoning: “Goal, Goal, Goal!”, indicating the UAV had reached the objective as verified by all three “goal cameras” pointed at the barrel. The final stretch involved the UAV flying back to the starting point and landing.

Sometimes a quadcopter would reach a point along the course and, inexplicably, hover as if dazed or confused about what to do next. After a pause, it would fly back to the starting point, having been programmed to do so if it didn’t know what to do next.

“I think it’s basically completely lost,” one researcher lamented after his team’s vehicle got close to the target in a clearing in the woods, but then took a wrong turn into another clearing and just kept going further away from the barrel. In that case, a safety pilot took over and landed the UAV so it wouldn’t be damaged, using the emergency RF link that had been installed for these experiments in the event a vehicle headed out of bounds or began flying erratically at high speed toward an object—which happened on several occasions. Undaunted by such glitches, teams would return to their tents, make some tweaks to the algorithms on laptops, upload them to the bird, and then launch again for another try.